“The self-emancipation of our time is an emancipation from the material bases of inverted truth.” — Guy Dubord, The Society of the Spectacle

In the last installment, I discussed the importance of coherence. That is, the importance of embracing, rather than avoiding, friction, as it is only through an honest engagement with things that challenge us that we can curve towards the asymptotic value known as ‘truth’.

In this instalment, I would like to do a deeper dive into the factors that drive us to shun friction in the first place, and how decentralization is a key component of averting this outcome.

Various thinkers, often with wildly different ideological convictions, have observed the same fundamental truth about human societies: that there is in fact very little truth involved in their creation and maintenance. Whether we call these untruths ‘memes’ or ‘collective fictions’, the underlying observation remains the same: humans require grand narratives and myths in order to function in ‘anonymous societies’. That is, societies that exceed the human cognitive capacity for recognizing the majority of other members of that society as distinct individuals with complex inner lives.

Rather, we use signalling to indicate shared culture — shared narratives — in order to display membership. The types of clothes we wear reflect a narrative about what sort of clothes we ought to wear. But they also show other members of our society that we belong, and can be used as a kind of shorthand for the sorts of things we value. In a mostly anonymous world, it sends a signal that we can be trusted to play by the rules.

But this is just the tip of the iceberg. Our lives are completely dominated by narratives, sometimes intersecting and sometimes contradictory. This is a fundamental part of being human, going as far back as our hunter-gatherer forebears. But, since the advent of agriculture, our societies have become larger and more complex — and our narratives ever more elaborate and abstract to accommodate them.

As with all aspects of human existence, this process accelerated after the Industrial Revolution, and has reached its zenith in the age of mass media. And, more so than ever before, in the age of social media. We have moved beyond mere narratives; the dawn of the industrial age brought with it the dawn of the Spectacle.

A World of Twisted Reflections

“In societies where modern conditions of production prevail, life is presented as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation.” — Guy Dubord, The Society of the Spectacle

A feature of modern economic production is an extreme division of labour. Indeed, this is what makes it all possible. Extreme specialization allows for maximum efficiency.

However, it also allows for maximum detachment and fragility. Each individual lives within a very small bubble, largely removed from all other aspects of production. They understand, abstractly, where the other goods and services in their lives come from. But this understanding is shallow in the extreme. How could it not be, when almost all the minute details of any given task are the purview of a specialist?

Outside of this very shallow awareness that things have to come from somewhere, the vast majority of material goods and services in a person’s life seem to come from an almost magical realm — appearing as if by the will of some ineffable god.

This is in steep contrast to the vast majority of human history, where all but a tiny fraction of elites had no choice but to be generalists, and to be intimately involved with most of the production that ensured their survival. Even those ‘specialists’ oversaw their craft from the beginning until the end. With rare exceptions, the material bases of life all came from within a short radius of where a person lived.

While we often look back at the peasant farmers of the past with condescension, scorning their superstitions and simple-mindedness, they were, in most of the ways that matter, far more aware of reality than most of us will ever be.

This modern mode of production comes with many economic benefits, but at the cost of our perception of reality. To reiterate: all human societies have narratives. But those narratives have always come into friction with reality — as a simple consequence of living off the land. Whether as hunter-gatherers, horticulturalists, farmers or herders, there is no way to ignore the consequences of environmental degradation, or climate change, or plagues. And almost the moment they hit, because the results were right in front of their eyes.

That is not the case today. Our capacity to create destructive externalities has risen exponentially since those simpler days, but so has our ability to insulate ourselves from the effects of those externalities. To the point that, when they do become too destructive to ignore, it’s already too late to do much about them. The COVID-19 pandemic is a perfect example of this, as it was only dealt with once it became inconvenient. When it was already much too late.

We see this too with Climate Change, where people only started to really take notice once it resulted in more extreme weather events and falling profit margins.

This is all facilitated by the Spectacle: a socially-constructed ‘reality’ that often bears very little resemblance to anything approaching truth. And if you only start to pull the thread of the reality sweater, you will find experts in almost every domain that argue most of what is commonly understood in this domain isn’t what is really going on. “Consensus Reality” is not particularly real and increasingly unstable.

The Addict

I’m sure many feel a resisting instinct to this notion of socially constructed reality. After all, even if society is trying to sell me on some bullshit, I’ll definitely be able to see through it eventually. I’m not a sheep.

But this is not nearly so simple. To understand why, I propose we observe this process using the metaphor of addiction.

What often starts small and harmless: early 1,800s Steam Locomotive Engine, Camera Obscura, Radio

Gradually creeping bigger: early 1,900s Cars, Electric TV

And more addictive,“I don’t have a problem”, 1950s Coke, Tanning beds, Plastic grocery bags

Full-on Spectacles self-deception, “I can stop whenever I want” , 1980s Subprime Mortgages, CFCs Spray, Spam

Glitches can’t be ignored further, “just one more time can’t hurt” 2000s CRISPR babies, Data-trafficking, Weaponized Nanotechnology

Justifications and delusions, and a reality constructed to not challenge those, ultimately all for the sake of continuing to feed your addiction.

There is a part of you that maybe recognizes what’s really going on, but you are not listening. And so as you spiral ever further and further down, continuing to make bad choices. And as things get worse, the delusions get stronger and stronger to support the gap.

Are we as a society not deeply addicted to the Spectacle, unable to engage with reality on many fronts? So many of our systems run on increasingly intense delusion and hyper-fragility.

The Complicated VS the Complex

In order to better understand what’s truly going on behind the scenes of our addiction, and how phenomena that did not previously exist within the scope of our understanding keep popping up and changing the entire category of the game, we must dive deeper into the concepts of Complex VS Complicated systems. These are formal concepts that have been crystallized nicely in the philosophy of science only over the last decade (Nonlinear, Far From Equilibrium). [Dave Snowden, 2]

In short, Complicated systems (including Boeing 747, Game of Chess, etc.) are finite and bounded. In such a system, all the individual parts — as well as their composition order — are well understood. Cause and effect are largely understood, and one can legitimately call himself an expert in such systems.

Complex Systems, by contrast, are always evolving and the phase space they can occupy are themselves changing. For this reason the relationship between cause and effect in complicated systems is strictly undeterminable. It’s impossible to predict how such a system will respond, because the system itself is “learning”: the qualitative characteristics are evolving. This does NOT mean these systems simply can’t be dealt with effectively — you just need a different approach. Which is to learn how to be responsive to its disposition with skillful difference to its subtle signals, and adapt to it. A good example of such a skill is surfing, where the individual surfer may navigate the surface of a complex system (the ocean) by paying attention to cues which only hint at what transpires beneath the surface.

Chaos Systems: in a chaotic system, even dispositions go away. There is no way of telling how to act, you must wait and pay careful attention, for when the system returns to complexity, for only then you can navigate.

Up until the 60s these weren’t even a category of thoughts, despite so much of our lives, and the things we care about most, being in the complex domain, simply because Newton (calculus, many of the laws of traditional physics) was so good at helping us to build useful stuff (e.g. cannonballs). As such, we have developed a bias towards linear science.

Square Peg, Round Hole

The systems we build are complicated, with many interlocking parts and many discrete roles for specialists. But still comprehensible when laid out in a diagram.

Most parts of reality, on the other hand, are complex. No matter how many diagrams we fill up with information, it will always be beyond the full scope of our comprehension — because the sheer scale of it means all the components interact with each other in unpredictable ways.

Specialization is a reliable means of solving complicated problems, but falls horribly short when confronted by complex problems. This is because specialization results, by its very nature, in constituent components working only at a single task, usually in ignorance of the other components. But complex systems involve all its parts influencing each other; in such cases, ignorance of other parts means failure. Often spectacular failure.

This can be seen in how the institutions in many countries failed to deal with COVID-19. The healthcare system, the media, and the financial systems may all be distinct and governed differently, but this just means that they each failed in a unique way. What is not unique is that they took complicated approaches to a complex problem, and remained isolated in their particular niches instead of collaborating in an open manner. The more “efficient” approach.

So, our addiction is to a lifestyle that prioritizes wealth over resilience, by optimizing for efficiency. This feels good at first — like taking a shot of amphetamine. But, just like taking amphetamine, you’re actually trading in future resources for an artificial boost.

We are addicted to a hybrid of efficiency and simplification of the complex, which allows us to overlook externalities and pull resources from the future

And like an addict reaching rock bottom, our externalities have accumulated to a point where their consequences break through the bubble. The construction that has separated you from reality dissolves and you can start to climb back to sobriety.

The Strongmen

Before we can think of how to possibly improve our reckoning better, and becoming more responsible for such unforeseen consequences, let’s note how we previously had the tendency of simplifying those consequences by connecting their emergence to intentional acts of either our leader or some kind of god. It is very tempting to buy into the idea of the strongman. The architect. The auteur. The phantom behind the curtain.

Humans crave a world of intentionality. A world with clear-cut causes with intuitive effects. It is often far more comforting to believe in a malicious intelligence causing all of our problems, as opposed to impersonal forces of chaos and entropy. On the flipside, it is comforting to believe that all we need is a benevolent usurper to replace this malicious actor in order to fix all of these problems.

However, nature is filled with examples of what appears to be intentionality, but isn’t. I previously discussed the examples of flocking birds and schools of fish, moving as though conducted, when they are in fact reacting in real time to their immediate environment — and each other.

Similarly, it seems that every successful business recently must break faith with the ethos that got it successful in the first place. We naturally assumes this to eval management

In other words, we need to understand that we already live in a decentralized world, and always have. This applies as much to human societies as flocks of birds. Every society is composed of individuals mostly just doing their own thing for their own reasons, far more concerned with their immediate environment, and their neighbors, than their government.

The Myth of Absolute Knowledge

Much of the dysfunction in the world can be traced to the same foundational myth. A myth that is even more delusional than that of the strongman: that absolute knowledge is both attainable and exploitable. How knowledge is defined — and which kinds of knowledge matter — has changed over time. For most of human history, the answers were sought through divination and sorcery. After the ascent of the Cult of Reason during the Enlightenment, however, the focus shifted to quantifiable data.

Since that time, the complexity of human societies has increased by several orders of magnitude. And although we have simultaneously advanced our information technology, every improvement in our ability to gather and process data has been accompanied by an acceleration in the rate of technological change. In other words, the better we are at gathering and analyzing data, the more data that we need to gather and analyze. We need to run faster and faster just to stay in place.

These approximations or epistemologies, tools to help us understand the world around us and collaborate (you write, I read and execute), sadly transformed into a clear and imminent danger in the industrial era of “toolmaking”. While humans are not unique in using tools — most animals with high intelligence have been observed using tools in the wild — we are unique in creating tools via abstraction. The use, deployment and refinement of complicatedness has been the mother of all inventions, the birthplace of the logic in technology. This is the point at which we no longer had any evolutionary precedents; while evolutionary processes are slow, parallel, decentralized, and unaware of their own existence, human-style tool making is serialised, centralised, and exponentially faster.

By observing only some inputs in exchange for only some outputs, and iterating endlessly until our tools are able to bend the space between this input and output while creating maximum externalities to all that’s unmeasured, yet we do all this without a shred of realization our apex predator mindset is inadequate to drive such unprecedented powerful abilities. No other predator has the capacity to kill the whole world.

Not an Apex Predator

Using a complicated approach to solve complex problems, we aim for our dashboard to one day tell us everything and, in the meantime, mess up with reality everywhere we can’t measure. Why? Simply because any epistemology that might appear on a dashboard is a slice of a ball — true to the logic of its creators and users. It’s for the humans, not for the ball. Some slices are better understood and predicted than others, but when we begin to believe that those high-fidelity slices can explain the entire ball, our understanding of the complex will alway fall short — blind to deep transformations happening outside of that slice.

Non-human animals can’t increase their game theoretic capacity much beyond natural selection within a given lifetime, so you don’t get radical asymmetries of power between predators and prey. Even before the advent of science, by contrast, humans used their sophisticated tools — their spears and atlatl — to hunt the megafauna of the last ice age to extinction. And this asymmetry has only grown exponentially since that time. Rather than coming to an equilibrium with the environment, we extract all available resources in one place, and then simply move on to extract the next one.

We remain in the evolution-inspired mindset of being the apex predator, but our capacities far exceed those of these predators in a manner that is evolutionarily unprecedented. We are a nuclear-powered invasive species, upsetting the entire global ecosystem.

But we depend just as much on this ecosystem as the species that we dominate. Our global parasitism will doom us if we can’t find a way to return to a self-stabilizing ecology. Any system that debases its substrate is a net bad for the world.

Not-So-Autocorrecting Markets

There is basically zero resemblance between the theoretical Adam Smith-type idea of markets as perfect, self-correcting, evolutionary, and meeting meaningful demand,and markets as they operate in reality.

The smartest people go to the best universities, to go work at the biggest tech companies, to master how to manufacture addiction for children more effectively. I don’t know about you, but this does not feel like ‘meeting meaningful demand’ or an ‘auto-correcting market’ to me.

To the degree there ever was such a thing — and we should bear in mind that the ‘free market’ of Adam Smith’s day was built on the aggressively literal corporate imperialism of the Dutch and British East India Companies — none of it is true today. The moment that you can manufacture demand, the logic of the whole thing is broken. Suppliers have an organizational capacity that the vast majority of consumers lack. Therefore, if suppliers see even a single potential customer, they can use asymmetrical manipulation tools to manufacture demand — sometimes out of whole cloth.

The idea underpinning the concept of the self-correcting market is that markets are subject to the rules of natural selection, where consumers have complete discretion to choose which competitors will survive, and this is what actually increases life quality for everyone. This is a cute idea that even in theory only works under extreme conditions of trust and transparency, and in reality doesn’t work at all.

Underneath most our problems are Massive Perverse Incentives — Multi polar coordination problems! (Nature worth more dead than alive, war and addiction are good for GDP) economic, defential power, some agents get ahead on the expense or other agent or the commons. Actors focus on what’s rational, only for them, and end up creating the worst possibility space for everyone else over the long term. No one is intentionally or maliciously doing bad things, but everyone is racing to do the destructive thing.

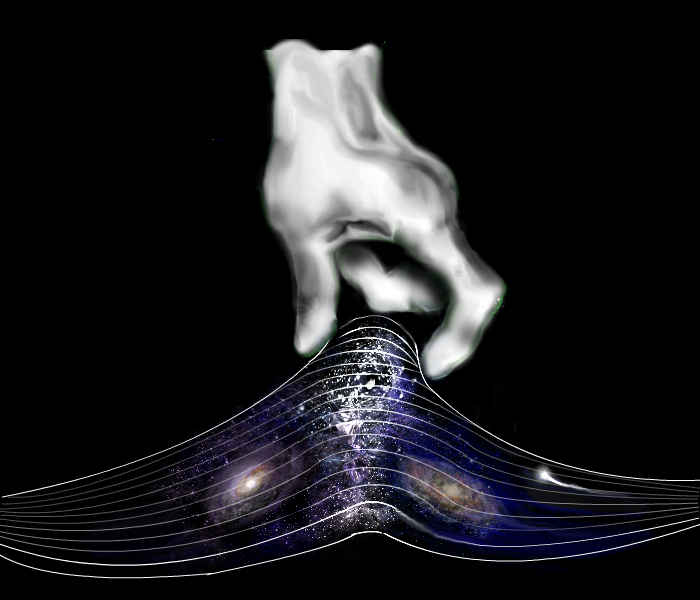

The Illusion of Top-Down Control

But a highly efficient, decentralized system of data processing already exists. Instead of aggregating data, analyzing it, and then deciding on a course of action, it relies upon the individual nodes of a network to process small, digestible bits of data and make localized decisions in real time.

This data processing system is what we call ‘society’. And ‘freedom’ is the degree to which the ‘administrators’ of society accept this reality, versus how much they try to interfere with it. Interference stems from the belief that their own analyses are more accurate — and have more predictive power — than that of the individuals who comprise the nodes of the network.

We now look back at the rulers of yore with disdain for relying upon astrology and oracle bones. Under the materialist paradigm, data is thought to be the ultimate scientific means of divining the future. Yet the proof is in the pudding: the machinations of planners are no more reliable now than in the past.

When the only certainty is constant and accelerating change, central planning is just another kind of soothsaying.The process that seems to have pushed this illusion into full-on delusion is the rate of change. Since prior to this acceleration, not much of technological note happened for decades, it was easier to sustain this illusion of control. Yet, since the rate of change itself accelerated, paradigms now come and go in a month, and the inability to respond properly in time is becoming the “emperor’s new clothes”.

What’s Decentralisation Got To Do With It?

Rather than thinking of decentralization and centralization as a dichotomy, it’s more helpful to conceive of them as existing at an intersection. The intersection of common good and individual optimization efforts (the degree to which we all get to enjoy it or specific corporations get to leverage their new findings, for example).

Once we understand that our societies are complex systems, where cause and effect are largely not well understood, and that our models and narratives are approximations and part of the Spectacle — heuristics of reality, but not the real thing — we can then easily understand how things we did not anticipate, such as a novel new behaviour pattern, emerge, or how a better model of approximation is invented.

We both create the global pie and collect our own share from it.

The more individuals spend time and effort on growing the total pie, as opposed to securing their share, the more we can improve not only the total size of the pie, but the environmental footprint and waste that we produce in the process of growing it.

Fairness as an industry.

If however the system we operate in encourages us to disregard externalities, we inevitably encounter feedback loops that fail to punish selfish or exploitative behaviour or reward actions that are altruistic. Play these loops a billion times, across multiple industries, and you get things like islands of trash in the oceans, widespread deforestation, and climate change.

So how can shifting the balance to more decentralization help to also shift these incentives?

It all comes back to the Spectacle. It is the extremely compartmentalized mode of modern production that allows for the extreme compartmentalization of human existence, and thus the maintenance of the Spectacle. And it’s this detachment and collective delusion that enables our most destructive behavior.

We have reached a point in our technological development, vis-a-vis the internet, where we can start to integrate into a cohesive whole. It is in fact centralized, top-down modes of production that encourage hyper-specialization, because such models allow for more predictability in the short term. It also means that specialists are more expendable and easily replaced.

While a certain degree of specialization is bound to happen in a more decentralized model, it won’t be the same kind of hyper-specialization. Indeed, the ever-shifting landscape of a decentralized model means that too much specialization can be a disadvantage for its individual components. It keeps people on their toes.

A decentralized system is one that is driven from the bottom-up by its components, meaning that the extreme level of detachment often seen in centralized systems is impossible. Though it may not restore us to a mode of subsistence where we see disaster coming with our own eyes, it certainly restores much of the healthy friction that is presently missing in our present paradigm.

The Collective Brain

There is a pattern that shows up time and time again throughout human history: great scientific and technological advancements often sprout simultaneously, or near-simultaneously, from multiple, unconnected sources.

We are all likely to recognize the name of Charles Darwin, but not so much the man who formulated a virtually identical theory at almost the exact same time: Alfred Russel Wallace. Popular culture likewise credits only Thomas Edison with the invention of the lightbulb, even though 23 other people had already built prototypes.

It’s also striking that, for all their cultural nuances, societies the world over tend to follow the same broad trajectory of social and technological development. Agriculture was invented independently in at least four places that had no contact with each other: the Fertile Crescent, the Yellow River Valley, the New Guinea Highlands, and Mesoamerica. Writing was likewise invented independently in at least three places: Ancient Iraq, Ancient China, and Ancient Mexico. The only clear unifying factor in all these regions was that they had passed a certain threshold of population size.

We see this pattern repeated over and over again, in both nature and human technology: the power and speed of a network is largely determined by the number of nodes in that network. And humans comprise a network all their own. As population size increases, more and faster communication becomes necessary in order for the population to manage itself. This leads to the invention of more efficient technologies, which further drives the population upward: a positive feedback loop.

This collective brain is excellent at problem solving, as well as building upon existing data. This explains why so many unique networks of humans, even when separated from each other by vast stretches of ocean and land, have come up with the same answers to questions like: “how do we feed so many people?” and “how do we preserve data accurately for future use?”

This also explains why inventions tend to happen multiple times simultaneously: each inventor is plugged in to the network and working with similar data. Indeed, it would be much stranger if there really was only one person coming up with every innovation.

An instructive example of the importance of population size and communication networks in maintaining and advancing technology is the aboriginal Tazmanians. They originated from mainland Australia, and arrived on the island with technologies typical of other aboriginal peoples. Bows and arrows, canoes, and fishing equipment. But they were cut off completely from the mainland. And, by the time they came into contact with Europeans, they had lost all of these technologies. Their isolation from the main ‘network’ of fellow aboriginal peoples, coupled with ecological factors which constrained their own population growth, resulted in technological regression.

This is an entirely bottom-up, decentralized process — and is largely unconscious. Most humans are not even aware that they are nodes in a network. We have reached a turning point, however. For the first time in history, these ‘neurons’ can connect instantaneously over vast distances. This has allowed us to improve technology at an unprecedented speed, but, as always, has drawn the covetous eyes of centralized institutions that wish to harness this power. Indeed, in some ways, the forces of centralization are becoming even stronger, because the power of the decentralized collective brain is likewise bigger and more efficiently exploited.

But we don’t have to settle for this!

For the first time in history, the Collective Brain can attain self-awareness. We have the resources available not only to make it more powerful than ever, but to make the ‘neurons’ realize their true potential.

We must acknowledge these “new” findings in complexity theory and the ever-increasing rate of paradigm shift, to support our claim that those who will adopt an abundance mentality, and sincerely play the long game, will rapidly outcompete those obsessed with the optimum-in-isolation and quick gains.

And blockchain will be one of the most effective tools to allow for this.