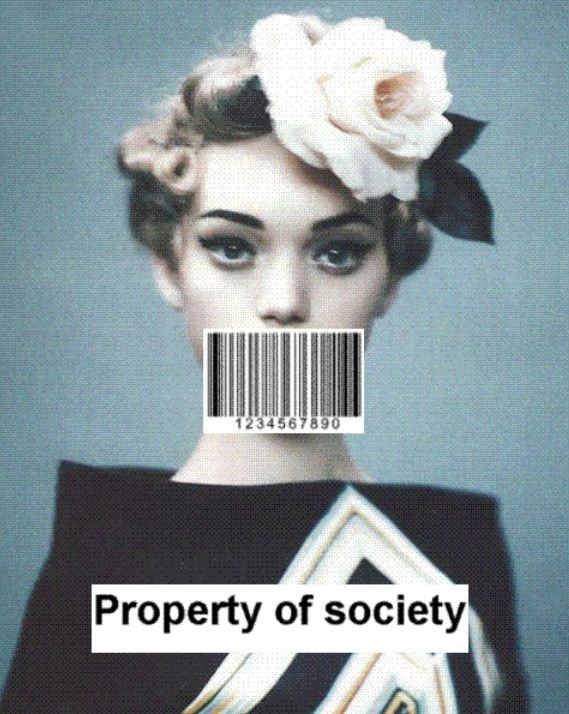

It’s really no wonder that so many teenagers and young adults waver between extremes of nihilism and rage towards the world as it exists today. They watch as adults lecture them about how they ought to live their lives meaningfully, while those same “adults” appear to be driving themselves crazy, in the very literal sense of being unable to distinguish between facts and fantasy. How is anyone supposed to figure out what’s really going on in the world? It’s only natural for young people to feel as though they’ve been betrayed, and that nothing really matters!

In a nutshell, this a breakdown of coherence.

Conversation is the primary tool we have for making sense of our world, and yet, without coherence, even conversation can’t do us much good. In this era of social media, all communication has become performative and all information has been weaponized. Agent Smith is correct: the vast majority of our conversations now are entirely useless.

There is something of a silver lining to this acid cloud, however. The many crises we face are interconnected in that they share a root cause: incoherence. And thus there is a strategy for beginning to solve them all simultaneously. With humans, everything begins and ends with abstraction: our mediated understanding of the world. The term “abstract” according to Hegel’s definition: The substitution of a part of the whole for the whole, the whole being “concrete”.

In the following few thousand words, I aim to show that while abstractions are necessary, and by no means evil, the process of amnesia that can result from these abstractions is an unmitigated force for evil in our world. The certainty that comes from this “forgetting we have forgotten” is a siren song that leads us to our doom. We extract facts from their holistic context in order to extrapolate convenient narratives that appeal to our need for order and control.

The first order of businesses is relearning what language and money mean. Both these miraculous things are not nearly as simple and transparent as they seem at first glance. They both rely on coherence and play crucial roles in sustaining coherence, and in shaping a complex system that is greater than the sum of its parts.

By the end of this essay, I hope you will agree that it’s well within our reach to create the conditions for the wellbeing of both our species and our planet. We are perfectly free to embrace a culture that will turn back-on the awareness that vitality cannot be given but can only be found.

We are not gods and shouldn’t pretend to be, our decades-old ‘factory’ to hijack and homogenize narratives into one super-narrative, to deprive nature of its own source of vitality, is not only misguided, but dangerous! Vitality must be discovered by our money and language, not created by them. The given patterns of spontaneity in nature are not only to be respected, but to be celebrated.

Satoshi Nakamoto’s contribution to humanity has been in showing us a viable path to release our money, and thereby our language, from this fundamentally confused paradigm. We FINALLY have the opportunity to create a people’s movement, a coalition like never before: a coherent meta-nation.

1. Don’t Think, but Look!

“How hard I find it to see what’s right in front of my eyes”

— Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Wittgenstein, an Austrian thinker-philosopher who deeply inspires me, argues that the challenge doesn’t lie in cleverness or intellectual flair. What’s really challenging, rather, is to be willing to see or understand the things that makes one uncomfortable. The realities that are at odds with the thoughts that bring us comfort and security. It is the lies we tell ourselves that are hardest to shake.

Wittgenstein died 70 years ago, having no idea how much worse things would get.

The legacy of the Enlightenment is a mixed one. On the one hand, it gave rise to the ‘blank slate’ fallacy of human nature, as well as the Cult of Reason (a topic which I will explore in much more detail in another writeup). However, it also gave rise to free inquiry and the marketplace of ideas. In other words, it encouraged people to truly think.

But nowadays, we cling to the very worst parts of this legacy while discarding its very best parts. People drift further and further away from what thinking really is — exercising their own judgment — and more and more into playing by a script. The vast majority of academics, scientists, activists, and politicians ‘self-censor’ their own work and ideas, in order to share views that are socially, politically, or even personally palatable. Researchers post works anonymously out of concern that going against accepted wisdom may harm their careers, while students complain anonymously about professors who dare to go against the academic orthodoxy.

There are times to shape the expression of our ideas in ways that are psychologically digestible, or even crafted to be attractive to an intended audience. But the more we do that, the more constrained we are from saying what we really think; the less able we are to look unflinchingly at the state of things and describe what we see, even if we don’t like what we find. If we never find ourselves in spaces of unconstrained openness, we might not even know what we really think, hiding truths even from ourselves.

There are many truths today which people are choosing to ignore, not because they do not see them or understand them, but because they do not want to see or understand them. Truth, as any philosopher knows, is a contested term. But perhaps in what is increasingly called a ‘post-truth’ age, the time is ripe to see the absurdity in how we now use language, and renew the battle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language.

In this world where truth is increasingly irrelevant, decades of pretence are coming to a close. Most of us are simply paralysed — stuck between false hopes. After years of denial, and years of desperate hope, we have finally reached a point where it is no longer possible to ignore the catastrophe that is almost surely upon us.

We seriously messed up and are gradually waking up to the reality that we’ve trapped ourselves in dysfunction.

We are woefully unprepared for the consequences of our actions.

2. Money And Language

”The two greatest inventions of the human mind are Writing and Money — the common language of intelligence and the common language of self-interest.”

— Mirabeau 1749–1781

So, what do I mean by relearning the meaning of money and language? To start with, we need to understand that money IS a kind of language. But we need to understand what language is in order to grasp this connection.

- Not nearly so simple: The first thing that must be established is what money and language are NOT. Familiarity, as they say, breeds contempt, so the ubiquity of money and language can lead us to the false conclusion that they are simple and readily understood. A transparent surface layer, concealing nothing deeper below.

That is, most of us mistakenly think the meaning of the word is in the word itself. But that is a kind of circular logic that doesn’t hold up under scrutiny. “Sky means sky because it refers to the sky.” Rather, the meaning of a word lies in how we use it in relation to one-another. Thus, the meaning is neither static nor absolute, but negotiated. Confused? For good reason. At the very beginning of “My Philosophical Development” Bertrand Russell tells how, until about 1917 — by which time he was 45 and had done nearly all the philosophical work for which he is now famous — ‘I had thought of language as transparent — that is to say, as a medium which could be employed without paying attention to it’. - It’s Something we DO: So, if it isn’t a static and simple communication protocol, then what is it? Money and language are signaling systems, which allow large groups of people to use shared abstract symbols to communicate and share. As Robert Boyce Brandom, an American philosopher, puts it: we are playing “the game of giving and asking for reasons”.

This stand in sharpest possible contrast to classical theory for meaning roughly asserted ‘the individual words in language name objects, sentences are combinations of such names. Every word has a meaning. This meaning is correlated with the word. It is the object for which the word stands’.

We now know the way we use these abstract symbols is dependent on context and subjective ideas, and it’s often the case that what’s actually being communicated using these abstract symbols is purely mental.

So the meaning of words, or the value of money, has nothing to do with an intrinsic value. Rather, these are mediums of exchange between people; their value lies in their ability to facilitate humans signaling. We can debate on “what is more just” or “which is more fair”, as if the essence of justice or fairness can be captured and defined! Yet such meaning can only ever be negotiated between people. One word can even have multiple meanings depending on the context — the “language game” — which are like genetic relatives that resemble each other, crisscrossing and overlapping, yet not necessarily having any single trait that all of of them share (which would qualify as ’Truth’). - It is not deterministic — A deterministic system is one with predefined inputs and perfectly predictable outputs. If money was deterministic, then the Keynesian approach of manipulating the economy via aggregate demand would be sensible. However, money does not work this way. Its value is based on multiple complex factors that are in constant flux, precisely because its value is determined by its users, and only when interacting with each other. It is the creativity of humans — the spontaneity, and the unpredictability — that makes it impossible for AI to build a perfect predictive model of the market.

The value of a dollar twenty years ago is not its value today. And the people who trade using the dollar have changed over the past twenty years. Similarly, language changes meaning over time: words that used to mean one thing shift to mean something else, or are lost forever.

The value of money and what it means is context-dependent, just like language. A man dying of thirst in the desert would pay any amount of money for water, yet the value of that same water to a man next to a drinking fountain is negligible. Like language, money only exists because it provides utility through meaning. - It is compatible with a ‘mediated understanding’ of reality -

The world is an unbelievably complex place, to the point where it overwhelms our individual cognitive capacity. To make up for these shortcomings, humans employ a ‘collective brain’ and thus become better problem solvers in large groups. But how can we manage this when other primates are limited to groups that rarely surpass one hundred individuals? The answer is that we make use of abstraction — a part of the whole that is sufficiently representative that it allows us to function — and weave those abstractions into narratives. This is only possible through symbolic language.

In these terms, money is the abstraction, and our monetary system is the narrative. Language is what we use to weave the narrative, but the narrative also impacts how we use language. They are inexorably linked, creating a feedback loop that is impossible for our species to escape. Every single human society, from the simplest hunter-gatherer band to the most complex, sprawling empire, was held together by these narratives built up from abstractions. - No private language nor private money — So, because the functioning of language relies on shared practices and narratives, the concept of a private language is nonsensical. Likewise, private money. Both of them only exist in the realm of reality-by-consensus, which is quite different from individual truth. They have no intrinsic value or meaning. Your money only has value insofar as someone else is willing to accept it in exchange for something that you value. If no one is willing to accept your money, then in effect it has no value.

- Existentially dependent on coherence — With this deeper understanding of the fluid nature of both money and language, the potential fragility of our narratives becomes clear. There is a delicate balance between strong foundations and fragile rigidity.

But now you’re probably asking yourself, “what does he mean by coherence?”. We’ve established that private language (and by extension, private money) does not actually exist. With this understanding in mind, consider the following thought experiment:

Imagine that every single person carries a box, and within each of these boxes is a beetle. However, only the one carrying this box can ever look inside of it to see what this beetle looks like. How can anyone be certain that the beetle in their box is the same as the beetle in the boxes of others?

The answer is: they can’t. But they can, perhaps, look up what a beetle is in an encyclopedia, or a dictionary, or by speaking with others. And they can therefore determine if their beetle in a box is reasonably close to being a beetle as defined by society. They also know with reasonable certainty that this external definition of ‘beetle’ is close to what other people’s beetles must be like, because there is no public dispute over the definition of beetle.

In language, coherence exists when the negotiated meaning of a word or concept is relatively close to that of the personal meaning as experienced by the vast majority of people. Take for example a simple object, like a pen: the overwhelming majority of people can agree on the particular qualities and characteristics something must exhibit in order to qualify as a pen: it must be narrow, oblong, capable of being held in the hand, and it must dispense some kind of ink. So, by this definition, the collective understanding of a pen’s pen-ness is coherent.

Things get trickier once we approach the realm of more complicated and abstract concepts. What is ‘goodness’? The negotiated definition of this concept is not entirely coherent across society as a whole, which is why political disputes even exist. Moreover, the definition of ‘goodness’ isn’t static even within the same social ‘tribes’ over time, whereas a pen will always be more or less a pen. By that same token, however, the concept of ‘goodness’ has a far greater impact on the way we organize ourselves than a pen ever will. This friction between the different meanings of important abstractions is not a bad thing by any means. This dialogue is part and parcel of coherence, because the meaning of complex abstractions cannot possibly remain static over time.

But why does any of this matter? And what the hell does it have to do with money?

3. There is no Trust without Coherence

One of the most profound perspectives of 20th and 21st Century science is that our world is wholly and enduringly interconnected. Basically everything that we thought to be isolated is in fact part of the same complex living system. This includes human beings, composed of numerous dynamic, interconnected networks of biological processes. Every whole has a relationship with and is a part of a greater whole, which is also part of something greater.

This relationship between the whole and its parts, and the “truth” of the whole as a means to resolve tension between different parts, is the heart of coherence. As with all living things, it’s not enough for a complex system to achieve equilibrium once. It must be sustained over time.

This is deeply tied to a phenomenon called emergent order. Observe, for example, how a large school of fish moves as though choreographed, in mesmerizing harmony, or how birds flock in murmurations. In both these cases, there is no global orchestrating power; the individual units are locally communicating with each other, based on feedback from their environment — ocean currents and air pressure, in these examples. The result looks as though it’s the word of a conductor — of some kind of higher intelligence — but it is in fact a spontaneous, bottom-up process.

However, there is a catch. This kind of spontaneous, cooperative behavior — order emerging out of apparent chaos — can only exist when the signals are clearly understood between individuals, and if the feedback from the environment isn’t obstructed in some way.

Coherence means that the world around us is comprehensible. Not just from an individual perspective, but from a collective one. This affects us at all levels of our lives, from whether we choose to cooperate with strangers to whether we choose to obey laws. When the only things tying us together are shared narratives, those narratives need to make sense.

People will inevitably behave in ways that maximise individual gain, leading them to hijack language and obscure signals. Sometimes consciously, and sometimes by accident. This is one way that coherence can degenerate.

However, once this process is allowed to run rampant, as in Capitalism 1.0, it creates a feedback loop that is very difficult to stop.

Difficult, but not impossible.

4. There is no Coherence without Friction

“We have got onto slippery ice where there is no friction and so in a certain sense the conditions are ideal, but just because of that, we are unable to walk. We want to walk so we need friction. Back to the rough ground!”

— Ludwig Wittgenstein

- The decision to entrust most facets of our lives to “experts”

- The decision to relinquish the gold standard as numeraire (more on this below)

- The decision to accept “Whig history” as the inevitable and superior end-points of all historical change

- The decision to vote only once every 4 years on a representative

- The decision to learn about the world from Facebook and YouTube algorithms

All of these are modern decisions in support of making the individual further “comfortably numb”: the Faustian bargain of abandoning friction in favor of scalability. A process of relying further and further on top-down broadcast modality, not realizing there’s a hidden cost.

Of course, we all follow scripts to some extent. This is an inescapable part of living in a society. We play roles based on gender, occupation, age, religion, and ethnicity. But there is a gulf of distance between heuristics for behavior and a nigh-robotic dedication to a very narrow and inflexible narrative.

At this point, you might be thinking: but isn’t that a contradiction? You’re saying that narratives need to be flexible; doesn’t a lack of resistance, of friction, make us hyper-flexible? Counter-intuitively, the answer is no. The “hyper-flexibility” that comes with abandoning friction is wholly illusory because it is done without any environmental feedback. Rather than adjusting narratives to fit with ever-shifting material and social realities, it becomes about ignoring material and social realities in favor of propping up existing narratives. This is the very essence of money-printing.

Authentic flexibility requires a source of resistance.

This is why it is notable that all the earliest forms of currency, from the coins of precious metal that Herodotus claimed were introduced by the Lydians, to the shell money used for millennia in Asia, Africa, and the Americas, were based around a finite resource that had little or no intrinsic value. Gold has special physical properties that makes it convenient as a medium of exchange — low reactivity and high malleability, for example — but its intrinsic value as a component in superconductive alloys wasn’t discovered until the 20th century.

One could even go so far as to call it a human universal that, wherever economic complexity passes a certain threshold, a commodity-based currency arises. Even the first attempts at paper-based currencies were still tied to a commodity.

This observation is not a value judgement. Human universals run the gamut from good to neutral to bad. But they are very useful to observe, as they provide us insight into deep, instinctive parts of human nature that cannot simply be ignored because they’re inconvenient for our pet ideologies or economic theories. They show us that humans and nature are not blank slates that can be shaped according to the whims of an enlightened, or not-so-enlightened, centralized authority.

The inner vitality of human beings and nature is to be discovered with our money, rather than created by our money. So the numeraire serves to sustain coherence for money. By vesting the meaning of money in a resource that can be measured, we create a source of friction between money as it is actually being used and the ideal of money as represented by the numeraire that doesn’t allow for easy ‘cheats’. When money is tied to a numeraire, work must be done to produce more of it. That is, when friction is present, choices carry an obvious and upfront cost. This is important, because all choices carry costs! But in a world where coherence has broken down, the relationship between choices and costs has been obscured.

Looking back at it now, it’s unbelievable how much arrogance it must have taken to ignore the lessons of history. To decide that we now know better than everyone who has ever come before us. But we were wrong. Coherence is hard, and that very difficulty is what makes it invaluable. It is a process that can only take place over time, where signals are constantly parsed from the underlying system. As with our own bodies, it is only through constant feedback that we can maintain homeostasis.

A society in coherence is one where expectations and reality align, where signals parsed from the system re-enforce this coherence, and reinforcement “policing” mechanisms help in sustaining coherence once initially achieved. Yet, as is so often the case, those who live in a coherent society — and especially those who are born into a coherent society — take that coherence for granted, and see its underlying mechanisms, and the friction they cause, as impediments to progress and growth.

Both language and money only work once in constant frequent use, with constant effort to re-enforced and advance coherence through friction. If money is a kind of language, then the numeraire (e.g. gold) serves as a kind of dictionary. By vesting the meaning of money in a resource that can be measured, we create a source of friction between money as it is actually being used and the ideal of money as represented by the numeraire.

Funnily enough, I surprisingly agree with Nobel-prize winning economist Prof. Paul Krugman, a famous skeptic of crypto currencies, that we are “taking a step backward”, from Fiat money (Modern Monetary Theory, Fractional-reserve banking, etc. ) to Crypto money, we go back to the rough ground, reinstating friction for the sake of coherence!

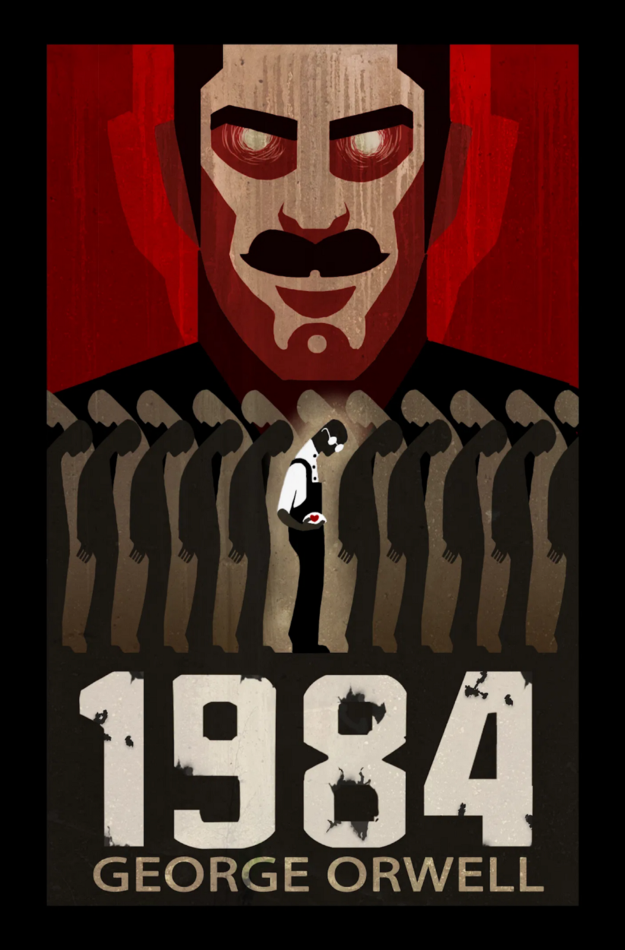

5. Monetary Newspeak

“The Revolution will be complete when the language is perfect. Newspeak is Ingsoc and Ingsoc is Newspeak“

— George Orwell, 1984

In the world of 1984, Newspeak was created by the totalitarian overlords of Oceania, with its fictional leader known as Big Brother, in order to actually limit free thought and free speech. In totalitarian governments, those in charge try to control every aspect of citizens’ lives, even down to personal habits.

The 20th century saw the rise of a new kind of money — one that was completely detached from any kind of numeraire: fiat money. This culminated in Richard Nixon unilaterally ditching the last remnants of the Gold Standard in 1971. In losing its ‘dictionary’, money became subject to meddling that would have been very difficult under the gold standard.

Hyperinflation was rare prior to the 20th century. It occurred in the Roman Empire in the 3rd century CE, as the result of diluting the precious metal content of its coins, and several times in China — which had precociously adopted paper money in the 9th century, enabling it to indulge in some of fiat currency’s worst excesses. But the 20th century brought with it an unprecedented wave of hyperinflation, in tandem with its adoption of fiat currency.

Hyperinflation is the result of a government either printing money in excess, or borrowing money in excess from its own central bank. Once we understand that money is a language, we can understand why this occurs: imagine, if you will, the government deciding that commonly-used words have new meanings. Imagine the chaos that would result as those who were obliged to use these new government-mandated meanings interacted with the general public. There would be a complete breakdown in communication. A complete loss of coherence.

Of course, most modern societies are fortunate enough not to experience hyperinflation. It’s just the most extreme culmination of a breakdown in monetary coherence: a real life reductio ad absurdum of the premise of fiat currency. This does not mean that the mechanisms underlying it are harmless in more stable economies, however. They’re just more subtle and insidious. And, indeed, the biggest danger lies in the problems that are not so readily apparent to us. In dysfunction that has become so normalized that we see it functional.

6. Prophets, Priests, and Soothsayers

Imagine if language was not only liable to be changed on a whim from the top down, but also had no dictionary to accompany it. How would ordinary people go about understanding these changes? They would probably turn to experts, and ‘experts’, who make such analyses their sole occupation.

This is in fact what we see in the modern global economy. Experts ‘interpreting’ the meaning of money, with experts to interpret those experts, etc. The result is so many layers of abstraction that any coherence that could potentially be parsed from the underlying system is utterly beyond reach. We worship at the altar of fiat currency, relying on the instructions of priests and prophets to illuminate its mysteries. The equilibrium of monetary coherence is impossible to achieve because the system is convoluted to the point of absurdity.

Indeed, our reliance on “experts” such as these is a classic example of friction avoidance. By not having to reckon with the absurdities and complexities of the system in which we operate, we create the illusion that everything is working just fine while the costs continue to accumulate — just out of sight.

And this has played a part in empowering an existing elite to monopolize an ever-larger percentage of the wealth we generate.

Though I do not think that this has been the result of conscious malice. These priests of money are, for the most part, providing a service to the best of their ability. They’re a symptom of our transition to fiat currency, rather than a cause.

7. Back to the Rough Ground

Before we make the last vital leap forward, let’s recap on key points:

- Coherence is humanity’s immune mechanism. Its restoration is paramount if we wish to improve the state of the world.

- Coherence emerges from healthy friction between different perspectives (private vs social; abstract vs concrete). As such, a marketplace of ideas is essential.

- From this lens, the aim to hijack and homogenize narratives is not only misguided, but dangerous.

- This evil insidiously permeates our lives by means of how we use our language and, most relevant to this piece, our money.

- We have been told that progress, growth, and innovation are best served by taking the path of least resistance. But this avoidance of friction will lead to stagnation, instead. In the end, it serves only to elevate rent-seekers who benefit from such stagnation.

And yet, in this game of Capitalism 1.0, it is not always clear who’s the master and who’s the slave. Due to the way that this system’s incoherence obscures the true costs of everything, even ostensibly positive endeavors can end up leading to much needless suffering. The Jeff Bezos of the world have undeniably provided us services that have made our lives more convenient, but at the expense of employee exploitation and small businesses being unable to compete. And these are just the costs we can readily see. What can we do, when “cheap” isn’t really cheap, because the true price is hidden?

To answer this question, consider this final point:

6. Both money and language must be decentralised, unhackable, and subject to organic friction.

Returning to a digital version of numeraire is a necessary but insufficient step to fix what we’ve broken. And I’m sure that many of you are rolling your eyes at the apparently absurd naivety of even suggesting that our current system can be reformed at all. But if there’s one thing that the post-internet era has proven, it’s that paradigm shifts do not need to be forced on anyone. For better or worse, bottom-up change is more easily achieved now than ever before in human history.

We are not gods, and shouldn’t pretend to be. If I want you to take one thing away from this piece, it’s that engaging with those who disagree with us is the only way for us to thrive as a species. Conversing a little bit more like Ludwig wants us to, remembering none of us holds a metaphysical Truth, our abstractions are not the whole thing. Rather mutual exploration for a super narrative, one that accommodates both our perspective, shedding new light on what we have known for long.

Without friction, there is no coherence.

So I propose that the only solution lies in leading by example. It’s so very easy to buy into the narrative that we are all players in a game with rules that can’t be changed, and that the only way to compete is to work within the existing paradigm — no matter how dysfunctional it is. I reject this, and call on you to reject it too. Capitalism 1.0 has most of humanity convinced that the finite game of self-advancement is the only one worth playing, but we have the means to prove that wrong.

Not only do we not need to wait for governments and other entrenched powers to wake up and smell the blockchain, our revolution can only really work if it comes from outside of the establishment. Outside of arrogant attempts to create a homogenized world where we smooth over the rough edges that give us a sense of the dangers in our path.

“A picture held us captive. And we could not get outside it, for it lay in our language and language seemed to repeat it to us inexorably.”

— Ludwig Wittgenstein, Genius Philosopher

- This article is a joined worked by Tomer Afek, Yael Hoffman, Dr. Doron Avital.

- Read more? PHILOSOPHICAL INVESTIGATIONS; Finite and Infinite Games, a vision of life as play and possibilities